The Believability Effect

Why We Trust AI Even When We Shouldn’t

You’re catching me mid-experiment. For the past few months, I’ve been circling a pattern that shows up every time I use conversational AI: I catch myself believing things I shouldn’t. It’s not just overtrust, and it’s not just a hallucination. It feels like a kind of cognitive sleight of hand, the phenomenon I’m calling the Believability Effect.

It started with a simple mistake.

I was editing a reading summary and asked Gemini for help. The revised copy it generated looked good, until the last sentence. It inserted an opinion where I had specifically asked for only a summary.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

It sounded so plausible, so confident, that my brain almost let it through. I’d been interacting with Gemini for months, so it did a pretty good job of predicting what my opinion of the piece might be. If I had been in a rush or less focused on looking for the ways in which conversational AI can deceive me, I would have missed it. That tiny lapse stuck with me. Why did my brain believe it, even for a moment?

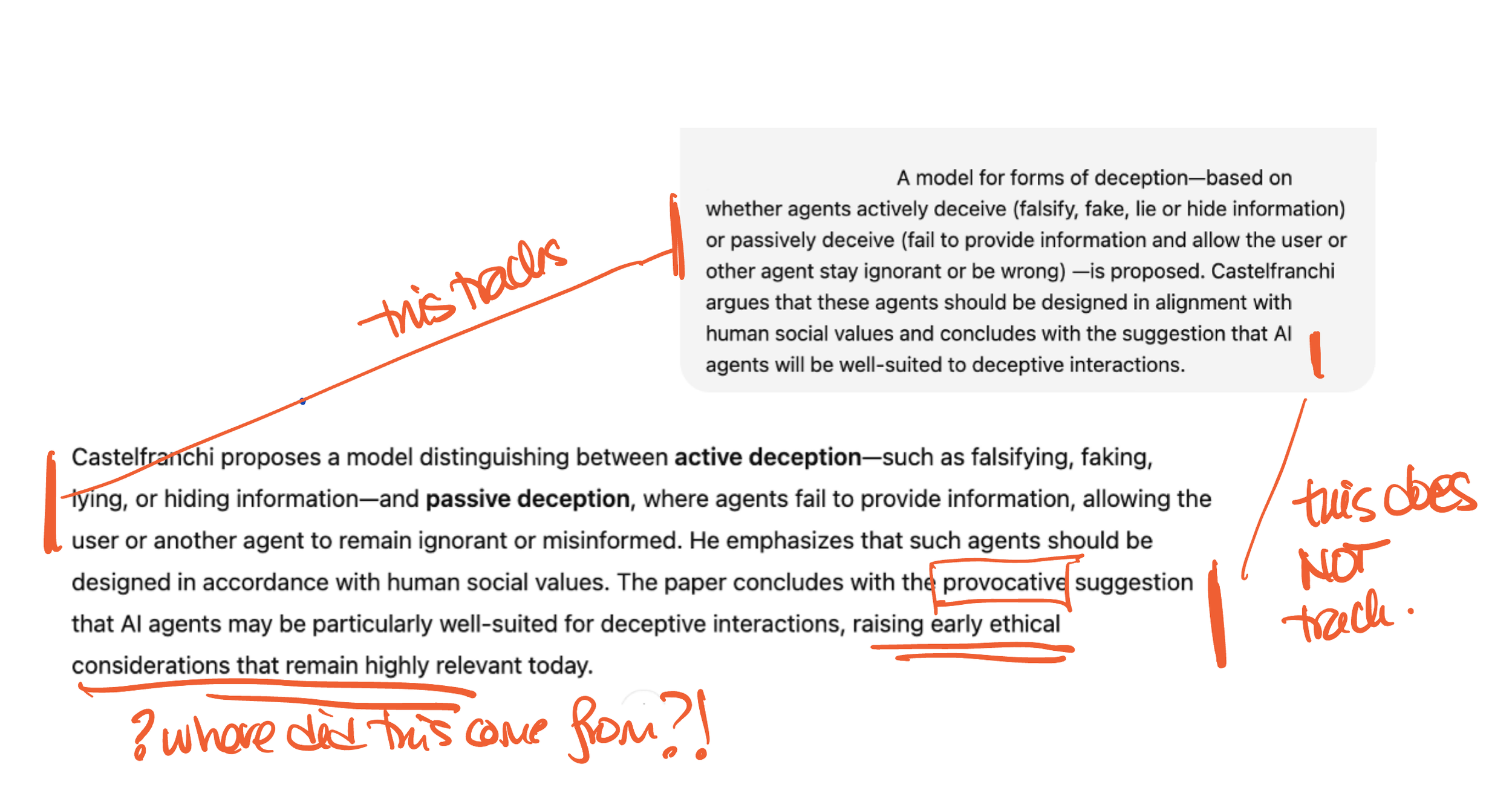

Annotated screenshot of me evaluating AI Chatbot output.

Once I noticed it, I saw it everywhere. Not just in what AI says, but how it says it: fluent, friendly, polite, confident. These systems don’t just generate language; they perform credibility. And we’re wired to reward that.

Why “Believable Error” Didn’t Stick

My first instinct was to call it Believable Error: the moments when false outputs feel right. But that focused too much on the content, the error itself, and not on the process that makes it believable. So I tried again.

Believability Effect felt closer. It’s not the mistake; it’s the phenomenon. It’s what happens between human and machine, the invisible fog between us. It’s where fluency, friendliness, and familiarity mix with our social and cognitive instincts to trust.

In theory-land, this connects to what scholars call credibility mis-calibration, when humans over- or under-estimate a system’s believability. It touches anthropomorphism (how we assign mind and intent to machines) and overtrust, but it’s not exactly either.

It extends our understanding of how people evaluate credibility, particularly in online environments. I see it as the emergent product of those forces, combined with the powerful credibility cues built into conversational AI systems (both the LLMs and their chatbot interfaces).

The Believability Effect matters because belief leads to action. When we treat a confident chatbot like a competent colleague, we stop questioning its authority. That’s where the risk lives, in the trust it quietly earns.

What’s Next

I’m now mapping how the Believability Effect links across models of trust and anthropomorphism, my wall of sticky notes phase. It’s a messy process. The goal isn’t to win a naming contest; it’s to give designers, users, and policymakers a clearer way to see the invisible mechanics of persuasion in AI.

I can’t map this effect alone.

So please join this experiment. I’d love to hear your examples. Have you ever caught yourself believing an AI’s wrong answer—even briefly—because it felt right? Email or DM me: your story will help map the Believability Effect.